Ways & Means

Ways & Means is an exhibition selected out of 185 applications from 33 different countries. The artworks chosen reflect in different ways upon a unique time in all of our lives. Many artists have been without their studios, materials, collaborators, or the time, space and funds to make work as they have in the past. However, out of these challenges, fresh approaches and new ways of working have emerged.

Ways & Means presents a range of these new approaches in an exhibition of work made during the Coronavirus pandemic.

Since 2016, Skelf has championed artwork that functions without physical form, allowing it to become more accessible and easily shared with a potentially global audience. These works are not the poor relation to something that takes place in real life, but a celebration of what is possible in the unlimited virtual space. The online platform has allowed us to exhibit artists from all around the world, and

Ways & Means reflects a range of experiences that capture something of the global phenomenon we all find ourselves in.

As most of our interaction with others has moved online, many of the pieces have focussed on conveying a sense of touch, or a bodily engagement with objects and artworks, as we attempt to capture what we miss through a screen.

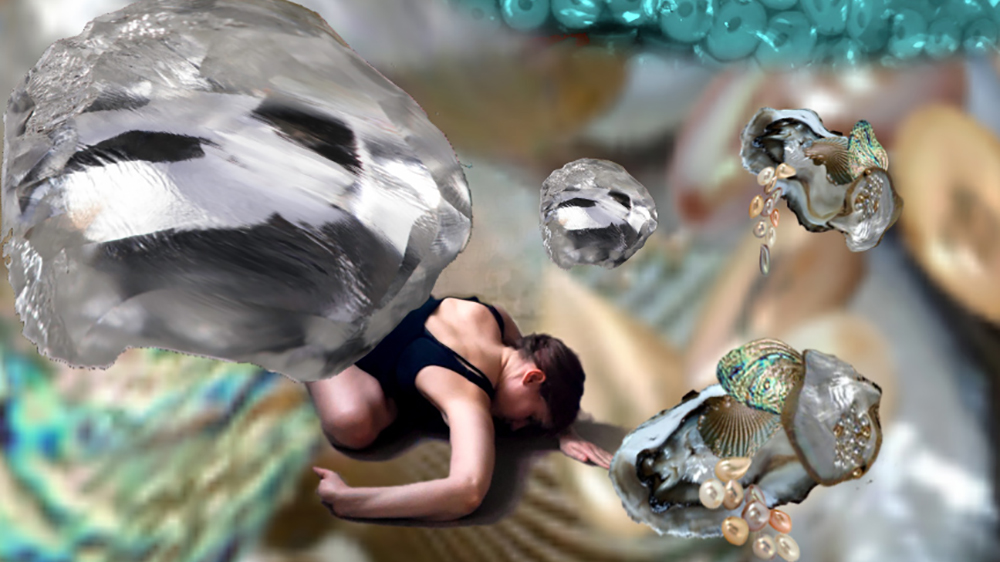

Laura Rouzet’s

The Feeling of Being collages digital elements that speak of haptic experience and

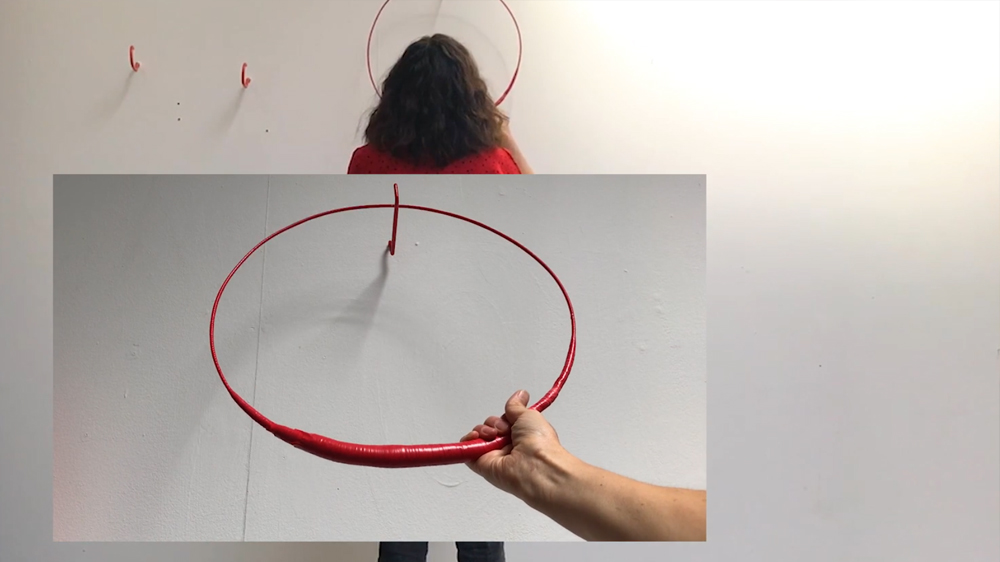

Kate Squires & Jenny Dunseath’s collaborative film

As Seen plays with the interaction between tactile objects and the conveying of their phenomenology across multiple layers of real and virtual space. Choreographer

Katrina Brown employs the subtle movement of gifs to create a sense of living breath.

Parallells are apparent between the work of

Sam Meredith and

Evangelia Dimitrakopoulou as hands touch and manipulate material- offering the viewer a vicarious experience that is both sensual and yet physically out of reach. Instructions become a vital tool as we attempt to share experiences while socially-distanced. Reflective of the instructional art of Sol LeWitt or the performances of Allan Kaprow, both

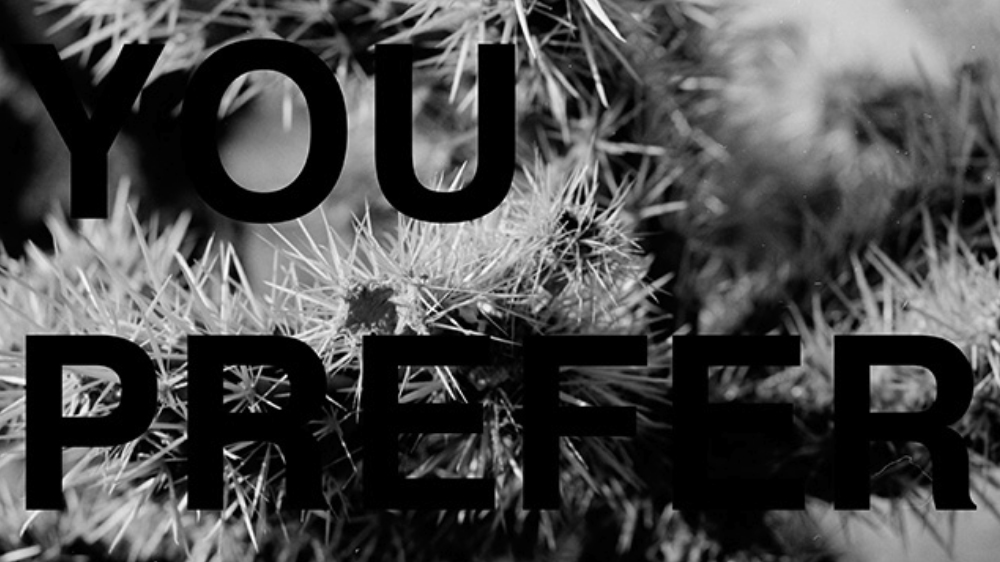

Alisa Oleva and

Leap then Look present propositions to the viewer, expanding the reach of their performative work into the domestic space of the audience.

The Black Lives Matter movement has achieved a powerful momentum during the pandemic, and has forced both institutions and individuals to reflect upon the changes they need to make to address the imbalance in our society.

Kevin Claibourne’s stark images pose difficult questions and are a powerful reminder that there will be no returning to ‘normal’, as things should not be the same again.

As video-calling has become a necessary substitute for face-to-face contact,

Ariel Dong’s work

Experimental Documentary of my Granduncle, made with the help of family members across the world, captures a sense of the multi-generational digital communications that have characterised many people’s lockdown experience. Several artists have employed existing online spaces for site-specific work, such as

Elin Lindecrantz’s

Tribute to Tinderman,

Sophie Cunningham’s online shop, and

Zoe Chronis’ ‘swiped’ collages.

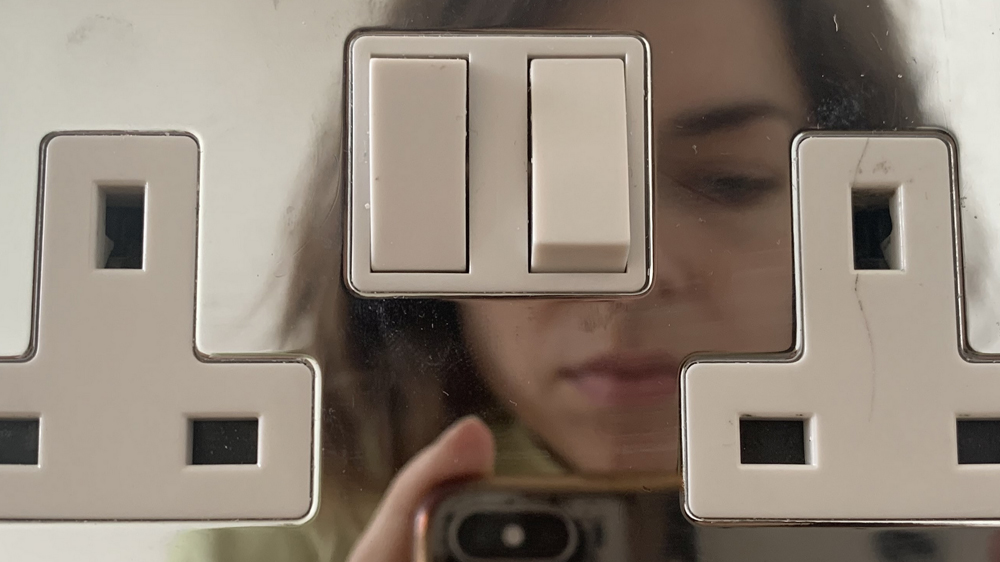

The artists’ studio usually feels a deliberate alternative to the domestic space of the home- somewhere to think and make away from the distractions of the everyday. For many artists, the outbreak of Covid-19 has meant that the two sites have become merged. The photographer

Ania Ready looks afresh at our familiar surroundings, finding beauty in the mundane. The collages of Brazillian artist

Laura Jost help us to see furniture as sculptural objects and

LOCKDOWN PAPERS by

Sarah Roberts offers moments of poetic clarity within her domesticity.

A restriction in movement draws our attention to the slightest variations in our view. While

Scott Pearce offers the viewer a close reading of his surroundings that becomes almost meditative in its duration,

Tom Patel presents an introspective stream of consciousness- in both, screens become windows and windows become screens.

As we put content out into the online world and hope for affirmation that someone, somewhere is listening, the role of the audience becomes more of support than recipient.

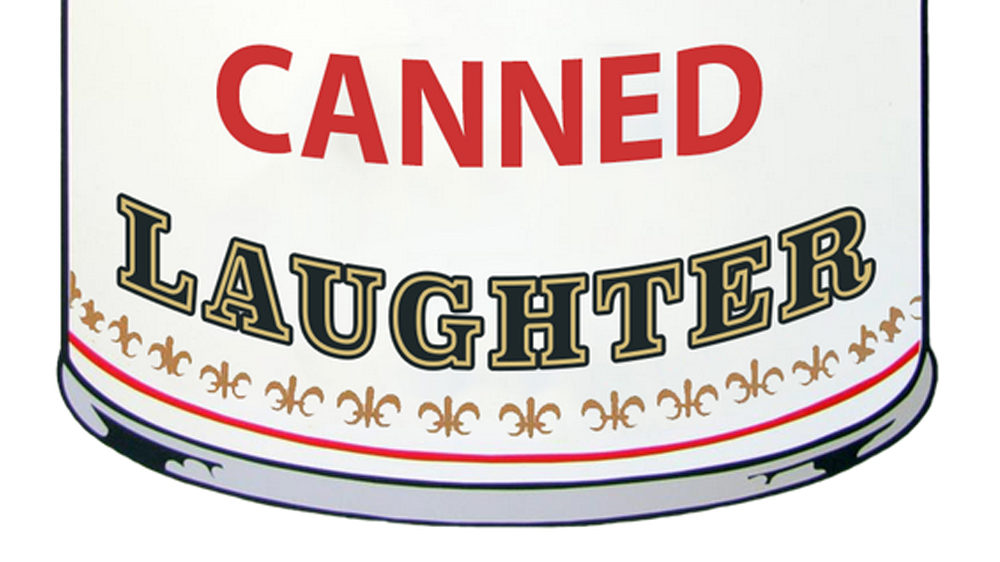

Like the piped-in crowds in empty sports stadiums,

Aidan Strudwick’s canned laughter creates an eerie solution for the performer without a crowd.

After four months of lockdown, ‘normality’ feels a fairly abstract prospect. The boundaries between the physical and virtual world have, through necessity, become blurred, and what is real seems now to be a blended combination of the two. Clearly, there will be no quick return to life as it was before. As the young voice in

John Lawrence’s work

Sturt e vant sings:

“good night real life, I love you real life…”